Having just finished writing a chapter that addresses, if only in passing, the crossed paths of antifascism and anticolonialism in the 1930s, this short piece in LRB on the career of Basil Davidson got me thinking about how the two related after the war:

This is Davidson, in a letter to the Times in 1973, protesting against a visit to Britain by Portugal’s head of state, Marcelo Caetano, after revelations of a massacre by the Portuguese army in Wiriyamu, Mozambique, the year before: ‘The known list of Portuguese massacres, large or small, is already a long one. The full list must be longer still.’ He goes on to cite an unreported atrocity in Guinea-Bissau, which took place ‘some 15 miles from the place where I was staying, in nationalist-held territory, last November’. In the same letter: ‘I would mention, if I may, that since 1967 I have made four visits to nationalist-controlled areas in Angola, Guinea and Mozambique … and have walked a total of some 600 miles there.’

In Davidson’s career, ground covered on foot signifies the slow assertion of the will, as real agency in the world: movement under pressure, off the beaten track, with comrades or like-minded people. But the will to what? The best answer, the defeat of Fascism, sounds a bit grand, but Davidson was a heartfelt anti-Fascist whose aptitude for this life-and-death struggle in Occupied Europe was then transposed to Africa, where white supremacist doctrines that struck a familiar chord had to be known and described. So he was off again, on foot, only now instead of bearing arms, he took notebooks: journeying with nationalist guerrillas and keeping the record were modest expressions of solidarity, in the struggle for decolonisation.

Edward Said on a 1979 meeting in Paris that seemed to involve big names and little ideas all tucked into Foucault's spartan apartment, in an old LRB piece that Abbas Raza at 3quarks brought my attention to:

As the turgid and unrewarding discussions wore on, I found that I was too often reminding myself that I had come to France to listen to what Sartre had to say, not to people whose opinions I already knew and didn’t find specially gripping. I therefore brazenly interrupted the discussion early in the evening and insisted that we hear from Sartre forthwith. This caused consternation in the retinue. The seminar was adjourned while urgent consultations between them were held. I found the whole thing comic and pathetic at the same time, especially since Sartre himself had no apparent part in these deliberations. At last we were summoned back to the table by the visibly irritated Pierre Victor, who announced with the portentousness of a Roman senator: ‘Demain Sartre parlera.’ And so we retired in keen anticipation of the following morning’s proceedings.

Sure enough Sartre did have something for us: a prepared text of about two typed pages that – I write entirely on the basis of a twenty-year-old memory of the moment – praised the courage of Anwar Sadat in the most banal platitudes imaginable. I cannot recall that many words were said about the Palestinians, or about territory, or about the tragic past. Certainly no reference was made to Israeli settler-colonialism, similar in many ways to French practice in Algeria. It was about as informative as a Reuters dispatch, obviously written by the egregious Victor to get Sartre, whom he seemed completely to command, off the hook. I was quite shattered to discover that this intellectual hero had succumbed in his later years to such a reactionary mentor, and that on the subject of Palestine the former warrior on behalf of the oppressed had nothing to offer beyond the most conventional, journalistic praise for an already well-celebrated Egyptian leader. For the rest of that day Sartre resumed his silence, and the proceedings continued as before. I recalled an apocryphal story in which twenty years earlier Sartre had travelled to Rome to meet Fanon (then dying of leukemia) and harangued him about the dramas of Algeria for (it was claimed) 16 non-stop hours, until Simone made him desist. Gone for ever was that Sartre.

Former TASPer Scott McLemee served up the new bio of Ernest Gellner with a huge scoop of ambivalence (though it's hard to tell how much SM intended that), also via 3 quarks:

One begins to see why Gellner, despite his range of reference and his intellectual energy, did not become a guru throwing a long shadow after he was gone. For these are not ideas that project either a clash of civilisations or the vision of some peaceful global civil society. He was anti-ideological but not post-ideological; there is a strong presumption in his work that conflict, healthy and otherwise, is built into the circuits of modernity. “A genuine commitment to rationality,” he wrote, “means that one must admit that it is poorly grounded, making it necessary to live without complacency.”

Beyond the world-historical drama shaping the circumstances of his first 20 years, Gellner led a life largely free of incident, apart from the occasional public controversy in the Times Literary Supplement. His biographer has had access to his papers and interviewed many colleagues and members of Gellner’s family, creating a portrait of someone far more genial in person than his writings might suggest. Critics who regard his work on nationalism as too detached from the phenomenon’s emotional core will need to square that judgment with the revelation that Gellner was prone to singing old Czech folk songs with gusto and considerable schmaltz.

Hall devotes a few chapters to the painstaking reconstruction of Gellner’s thinking on particular topics in philosophy and social theory. This is a necessary task given how little secondary literature there is trying to synthesise his work, though it often feels as if a set of monographs had been stitched onto the biographical frame, rather than integrated into it. But the cumulative effect is monumental – and a monument does seem overdue.

NYTimes reviewed Bruce Cumings' new book on the Korean War, reminding me to put it in my Amazon queue for when I have time and money.

Vinay Lal, whose writing I usually like, did a pretty bad job reading Indian American outrage over Joel Stein's stupid column on Edison, NJ:

In India, some writers and media broadcasters have not fully understood the emotions that are understandably aroused when Joel, adverting to the fact that townsfolk started referring to the Indians as “dot heads”, adds by way of trying to be ironical: “In retrospect, I question just how good our schools were if ‘dot heads’ was the best racist insult we could come up with for a group of people whose gods have multiple arms and an elephant nose.” Caricatures of a religion never go down too well with its adherents; moreover, there is a lasting memory, especially in New Jersey, of a previous chapter of racial history when the “dot busters” went around assaulting Indians and even killing a couple of them.I have a number of problems, but here's the short of it: (1) criticizing touchy Indian Americans as a whole but not citing or quoting any of them in particular is bad practice; (2) none of the anger I read--and there is no doubt a bias in what desi sources I do and don't bother with--was couched in the language of religious offense; (3) I think Lal badly underestimates the legacy and the reality of anti-Asian violence and the "even killing a couple of them" line is bitter, heartless, and stupid (and I wish he'd take it back); (4) the overly broad strokes here sweep under the rug entire complex histories and lineages of Indian American politics and culture; (5) this reminded of the feeling--since forgotten--I had when I read Lal's The Other Indians: "This is written as if the entire field of Asian American Studies never existed."

Indian Americans, on the other hand, give every appearance of being a trifle too sensitive. They have accepted the designation of ‘model minority’ with gratitude, scarcely realizing that the term was less a recognition of their achievements and more an admonition to African Americans and Hispanic Americans to shape up; consequently, they feel all the more slighted by Joel’s apparent characterization of them as undesirable. If an ‘over-achieving’ community could be so easily slighted, what hope is there for immigrant communities or ethnic groups that are less affluent or less characterized by high educational achievements? This is a reasonable enough claim, except that Indian Americans have never been keen on expressing their solidarity with less affluent or otherwise stigmatized communities. Moreover, much of the anxiety stemming from Joel Stein’s unimaginative attempt at humour owes its origins to the widespread perception that Indian Americans are an ‘invisible minority’, whose decency and relative distance from the mainstream of American politics has rendered them susceptible to onslaughts and humiliations that would never otherwise be imposed on a community otherwise distinguished by its affluence, attainments, and general reputation.

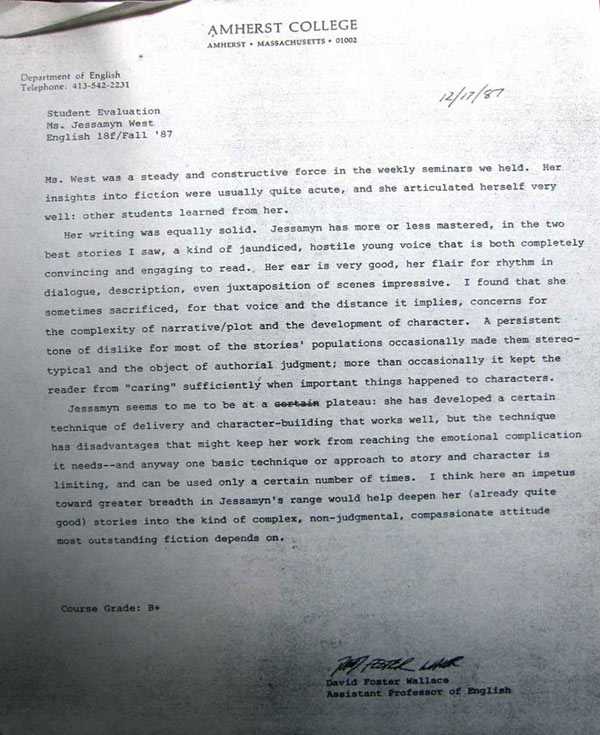

HTMLGIANT brings us a 1987 student evaluation by David Foster Wallace:

I'm left with two thoughts: (1) MFA student evaluations would make great material for a study of the politics of literature; (2) if I had been the student who received this evaluation I would have immediately written a bright, burning, entirely simplistic, judgmental, and cruel fictional portrait of DFW in response. Just to get it out of my system.

Also noted:

NYT reviews Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Steward, Professor, Tattoo Artist, and Sexual Renegade and Freedom Summer: The Savage Season That Made Mississippi Burn and Made America a Democracy.

I enjoyed this line when I reread CLR James's review of E. Wilson's To the Finland Station: "Some day when a materialist history of history is written, it will be a marvelous verification of the Marxist approach and one of the most comic books ever published."

Now back to interpreting a little known text written in Mexico in the winter of 1919...